Due to concerns regarding government repercussions, the writer of this piece writes under the pen name “Sloane Song.” Human Rights in China has independently verified the identity of the writer.

December 26, 2023 marked the fourth anniversary of “12·26 Xiamen Gathering Case,” in which lawyer Ding Jiaxi was arrested. On this occasion, Human Rights in China is releasing a serialized feature dedicated to Luo Shengchun, a human rights advocate, as a tribute to her unwavering efforts. This feature acknowledges her relentless dedication to seeking justice for Chinese prisoners of conscience, including her husband, Ding Jiaxi, and advocating for human rights and freedom for the Chinese people. The feature will be divided into five parts, unveiling various facets of Luo Shengchun. A special thank you to Luo Shengchun for generously sharing intimate details of her life, allowing us to see her not only as a courageous and conscientious civic activist but also as a wife, a mother, and a woman with voice and attitude.

This piece will be published by Human Rights in China one part at a time, over five weeks.

Writing in her diary on April 23, 2014, Luo Shengchun imagined how a “great wife” would write to her imprisoned husband:

“Dear husband, you don't know how much your influence has changed me. I have now become a New Citizen advocate. I help organize your recordings and share them. From your recordings, I have gained a deeper understanding of your ideals of a civil society. You are gradually transforming me from a woman who only knew about romance into a woman who cares about society, who has ideals and a broad mind, and who shares the worries of the world and rejoices in its joys... I will continue to support you, understand you, until the day you are released.”

Luo believed that this “great wife,” with devotion to a democratic China, was the opposite of herself, a “little woman.” When Luo left China with her two young daughters and arrived in the United States in 2013, after her husband Ding Jiaxi, a human rights lawyer and one of the leading figures in the New Citizens Movement who was sentenced to three and half years in prison, she thought only by suppressing her emotions and conforming to her husband’s expectations could she be the “great woman” with ideals for her country and civil society.

During her early years away from her husband, Luo saw herself as a “little woman,” confined to the realm of affections and romance. In those days, when she corresponded with Ding, her letters were imbued with her sorrow and bitterness, with words like “you always tell me to love you in the way you like, and I have done that, and I’ve been doing that for many years. But have you ever thought about loving me in the way I like, even just once? I don’t need it for a lifetime, just one time, a real one...”

Nine years later, on April 29, 2023, three weeks after Ding was sentenced to 12 years in prison for “subversion of state power,” and his New Citizens Movement peer, Xu Zhiyong, a legal scholar, was sentenced to 14 years in prison, I met Luo at Democracy Salon in New York. Later, in June and July, I interviewed her at her apartment in Virginia, and Luo shared with me her correspondence with Ding. Luo told me that she still deeply, painfully loves and misses Ding, but her world is now much bigger than that. “I believe I’m standing on the same level as he is now,” Luo said. “I am determined to continue the cause of my husband and Xu Zhiyong. I’m determined to be a woman with a voice and attitude, be a real citizen!

Now, Luo’s only question is how to bring her Jiaxi back home to the US from the dictator’s regime, from the CCP (the Chinese Communist Party).

I.

Luo Shengchun’s husband, Ding Jiaxi, now 56 years old, is a prominent human rights lawyer in China. Born and raised in a humble village in Hubei Province, Ding initially pursued a career as a jet-engine engineer after attending Beihang University, a prestigious science and technology institution in Beijing. While in college, he joined the 1989 Democracy Movement and identified with the concepts of anti-corruption and democracy, but was called back to school by his teacher for finishing an urgent paper on the night of June 3, when the violent crackdown unfolded.

After working in an aircraft engineering institute, Ding returned to Beihang University to pursue post-graduate studies, where he met Luo in 1992. It was during this time that he developed a keen interest in law, and dedicated his spare time to self-study. After passing the bar exam in 1994, Ding started his professional career as a lawyer with a concentration on civil law. In 2003, he founded his own law firm, Dehong.

Luo recalled that as a commercial lawyer, Ding lived large. He used to spend 100,000 CNY on golf per year, enjoyed five-star hotel stays, and ate expensive dishes such as bird nest soups and abalone.

Being a successful lawyer not only brought Ding comfortable living conditions, it also exposed him to the injustice in society. By the time he attended Fordham University School of Law in the United States as a visiting scholar, he had already developed a strong determination to dedicate himself to the social movement in China. This period provided him with the opportunity to engage in discussions with fellow scholars. Upon his return, he had transformed into what Luo referred to as a “veteran angry youth.” He became increasingly disheartened by the lack of freedom of speech and the injustices prevalent in the social news he encountered. Meanwhile, Ding collaborated with human rights activists and legal scholars, such as Xu Zhiyong, in the New Citizens Movement, and embraced the principles of the New Citizens Movement: Freedom, Justice, and Love.

In 2013, Ding was detained as part of a widespread crackdown on activists and lawyers in China, charged with “gathering a crowd to disturb public order” and received a three-year and six-month prison sentence. After his release, in the fall of 2017, Ding visited Luo and their daughters in the States for two months. On December 26, 2019, Ding was arrested again, and in April 2023, he was sentenced to twelve years in prison for "subversion of state power."

The above paragraphs summarize the story of Ding Jiaxi, a prominent defender of human rights in China, the beloved husband of Luo Shengchun, her “only one in this life.” It is a narrative that Luo has recounted to journalists time and time again, a story that journalists have requested from her over and over again, a tale in which she only exists as a supporting character, yet this story has come to define her very identity.

To comprehend Luo Shengchun, her love for Ding, and her personal journey, one must not leave out the chapters of Ding’s story. Yet, that is only one fragment of Luo’s own narrative, in which she stands as Luo Shengchun first, before ever being known as Ding’s wife.

II.

“The more I understand Jiaxi and his ideals, the deeper I love him,” Luo Shengchun told me. “Our love started as corporeal and affectionate, yet it has transformed into a spiritual connection. I felt the purpose of life when I was around him, whether as a wife or a mother of our kids. I didn’t know who I was before, but now I see clearly who I am meant to be: a person with a sense of responsibility for society, who is passionate, willing to sacrifice, who carries a mission.”

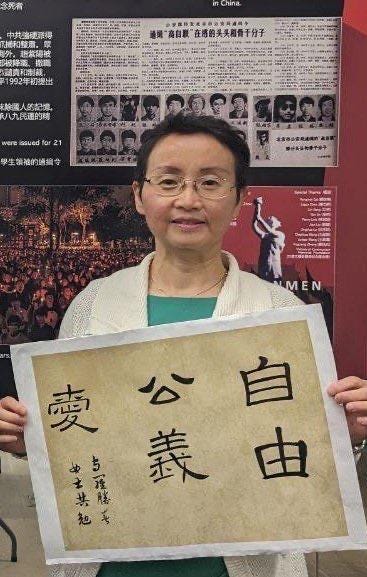

April 29, 2023, New York. At the memorial museum of Tiananmen Square massacre, after a seminar about Xu Zhiyong, Ding Jiaxi, and the Citizens Movement that promotes freedom, righteousness, and love in China.

LuoShengchun, aged 55 this year, stands at just over 1.5 meters tall and weighs less than 130 pounds. With short curly hair, long and slender eyebrows, she always smiles with her eyes. On important occasions, she applies makeup, outlines her eyebrows, and puts on lipstick. She wears 5-centimeter-high black high-heeled shoes to exude a stronger presence, yet she often complains about how painful these shoes are to walk in. She enjoys practicing yoga and swimming. She has a fondness for the crispy skin of chicken and duck, considering them incredibly succulent. She also savors Mediterranean cuisine, using the complimentary pita bread to dip into olive oil and various spices whose names she can’t quite recall. In her home, the floors are made of wooden planks. She delights in the feelings of walking barefoot on them during the summer. When we conduct interviews, she takes the time to brew a pot of green tea, peel a pear, and settle into the single armchair opposite me. She sways gently, one foot resting on the chair, wrapped in a blanket.

Throughout the interviews, Luo’s voice occasionally faltered when she spoke about her two daughters. She told me that she sometimes found a semblance of her daughters reflected in my presence.

III.

In the fall of 1992, at a thermophysics experiment lab at Beihang University, the 24-year old Luo Shengchun met the 25-year old Ding Jiaxi. She was in the lab struggling with her thesis when Ding walked in with “the most captivating, sunny smile” she had ever seen. For Luo, it was love at first sight.

“Hello, shi jie!” Ding warmly greeted Luo. In China, shi jie, which literally means academic senior sister, is a respectful way to greet a female student who goes to the same school but in a higher grade.

Luo felt like that was something intimate, genuine in his smile that she hadn’t seen in the smiles of others. Not a polite smile like a mask, but a kind of sincerity she could touch and trust. “I was completely melted by his smile,” Luo recalled.

Luo started her graduate studies in the field of biomedical engineering at the Department of Engineering Thermophysics at Beihang University two years earlier than Ding. She identified herself as a person “depressed by nature, introverted and pessimistic” at that time.

Outside of the laboratory, the 24-year-old Luo Shengchun was in her prime. Boys from other schools frequently visited her, and Luo would take them out for meals, though she never accepted any of them as her boyfriend. When Ding Jiaxi returned to Beihang University for his graduate studies in 1992, their mutual advisor warned him, “Be cautious when approaching Luo Shengchun; she already has a legion of admirers.”

Shortly after their first encounter, Ding started to passionately show his affections for her. She was head over heels for Ding, but she didn’t want him to know, so she presented herself as a reserved shi jie in front of him. He sent her flowers, bundles after bundles of roses, and wrote her many love poems, which Luo found adorable but at the same time, tacky. He invited her out for meals or to go skating, and Luo would suppress her excitement and turned him down a few times before she said yes. He showed up in her lab and around her dorm all the time with different excuses, and while she pretended to ignore him, she in fact wouldn’t be able to concentrate on her work. Whenever she was around him, she felt like “my heart would flutter like a startled deer.” Luo guessed that to some degree, he must have known her feelings for him too.

Ding and Luo started dating during the winter break, and from then on, their relationship blossomed into a carefree young love. When spring arrived and the new semester began, Luo would often sit behind Ding on his bicycle with her arms wrapped around him. Ding would be by her side, keeping her company through the late nights of paper writing.

In February 1993, Luo began working at the 304 Institute of National Defence Industrial Department. She wholeheartedly supported Ding, who aspired to a career as a lawyer at the time. Despite Ding’s limited availability for dates, simply being around him made Luo happier than ever. Once a melancholic person, Luo found herself crying less, laughing more, and more willing to go out and meet new people.

“Jiaxi completely changed my whole outlook on life and the future,” Luo said at the 14th Annual Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy in 2022. “After we began dating, my college friends barely recognized me, as Jiaxi brought out the sunshine in me.”

IV.

In 1968, two years into the Cultural Revolution, Luo Shengchun’s mother wanted to have an abortion. She was 39 years old, and her husband had just been sent to a farm for “labor reform.”

By then, Luo’s mother was already raising four boys and a girl on her single salary as an accountant in a rural village. She didn’t know how she could support one more child in the family. But as she stood in front of the hospital, she decided to keep the baby. What if by some stroke of luck, she wondered, the higher-ups decide to show a bit of kindness, considering the newborn baby and sparing Luo’s dad from being sent so far away?

In October, Luo Shengchun was born in Jiangxi Province. Her birth didn’t change her father’s fate of working in a labor camp, living in a a foul-smelling cow shed, on the verge of suicide, Her mother single-handedly shouldered the household responsibilities. When her father made occasional trips home for a day or two during the Spring Festival, he would sit with her under the covers to read poetry from Tang and Song dynasties together.

Luo understood her mother was going through a lot. At the start of the Cultural Revolution, her sister was forcefully had half of her hair shaved off, a common practice back then to humiliate people. One of her brothers was denied the opportunity to attend junior high school. Another kid once taunted him for being a “labor reformed prisoner,” he erupted into a fit of rage and almost beat the boy to death. He was then diagnosed with bipolar disorder, often running away from home and relying on pills to fall asleep. Luo’s mother wept day and night for him, traversing twenty kilometers on foot to retrieve his medication from the hospital as she couldn’t afford a bus ride .

All the other women in the neighborhood appeared to have many friends and were always chatting, yet her mother was isolated. Night after night, she returned home after long hours of work, hastily ate dinner, and then continued her side jobs to support their family of seven. Luo thought her mother must be sad and lonely. Sometimes, she wondered how her life would be different if she had been born into a different family.

Amidst an era engulfed in political fervor throughout China, Luo gradually grew up. She used to cry a lot for reasons she can no longer remember. She could sense that certain aspects of her life lacked meaning and coherence, feeling small and inconsequential in the vast expanse of the world. What is my purpose in this world? she wondered. She couldn’t find an answer, and she was always a bit unhappy.

“The melancholic temperament within me was ingrained since the time I was in my mother’s womb, a product of her longing for my father during the Cultural Revolution.” Luo wrote in her diary on February 25, 2014. “Now, I find it difficult to let go.”

The first Chinese characters she learned in school were “毛主席万岁” (Long live Chairman Mao) and “共产党万岁” (Long live Communist Party). She didn’t comprehend the meaning behind these characters, but she was always at the top of her class and never talked back to her teacher. Luo was a typical good student in the Chinese educational system. In elementary school, she was among the first to proudly wear the red scarf of the Young Pioneers, and in junior high school, she was part of the first wave to join the Communist Youth League of China. These political advancements were regarded as accolades bestowed upon obedient and academically successful students.

“I was indeed an obedient and well-behaved girl,” Luo chuckled. “When the teacher assigned the class to write a phrase one hundred times as a punishment, I diligently complied. My mom used to say that I treated every word from my teacher as if it came from the emperor."

V.

Luo Shengchun was only seven years old when Chairman Mao Zedong died in 1976. She observed the people around her engulfed in howls and wails of grief, seemingly devastated by the news. Why are they crying? she thought. And who is this person?

“You know Chairman Mao?” others asked through tears. “How could he be dead? He cannot die!”

Not sure what better to do, Luo mustered some feigned tears and joined the mourning crowd.

From a young age, Luo’s mother had instilled in her the importance of avoiding discussions of national affairs and steering clear of politics. She believed that one needed to follow the adage of “closing both ears to external matters, and dedicating oneself to the study of sage books.” Upon entering high school, Luo chose the science track instead of the humanities track. Despite her deep interest in literature, Luo believed that pursuing literature was a luxury she couldn’t afford. Studying science would help her to secure a stable income for her family.

In the spring of 1989, when Luo was a junior at Dalian University of Technology Power Engineering Department, waves of student protests erupted in Beijing. The April 27th Mass Demonstration, joined by thousands of people, the students’ hunger strike, and slogans of “We Want Freedom!” “We Want Democracy!” and “We Want Human Rights!” reverberated from Beijing to the rest of the country, including Luo’s school.

Having read through literature that reflected on the Cultural Revolution, Luo almost immediately identified with the values of this movement. She was always the first to join the local protests and the last to leave, leading from the front, and even helped make signs and chant slogans. Unlike many other students who believed that traveling to Beijing to show solidarity and support was crucial, Luo thought that for the movement to have a truly transformative impact, it needed to mobilize the masses nationwide.

Back then, Luo was unsure of the exact events that unfolded in the early hours of June 4, where hundreds of students and civilians lost their lives in the face of military tanks and gunfire. She imagined there were guns. It was not until years later when she came across the images of tanks crushing unarmed protesters. She decided to halt her activism in Dalian, and at the same time, set her sights on pursuing her graduate study in Beijing and uncovering the truth for herself.

When Luo arrived in Beijing in 1990, discussions of June 4 were strictly prohibited. Consumed by academic pressure, she gradually pushed the pursuit of truth to the back of her mind. However, deep within her, there remained a lingering sense of doom regarding China’s future. She diligently studied English. She yearned to study abroad and see the bigger world.

That is, until she met Ding Jiaxi in 1992.

VI.

After they started dating, the first question Luo asked Ding was why he wanted to be a lawyer.

“I’ve seen many people who couldn’t speak for themselves since I was young,” Ding said. “I want to be a lawyer so that I can speak up for them. There are so many ugly things in society that I want to change. I’m going to be a lawyer first, and then a judge, and then I’ll establish a more comprehensive legal system.”

Luo found Ding to be very ambitious. He was the only person she knew who would engage in discussions about these grand social ideals. Back then, Luo didn’t have her own idealism, but she found joy in listening to Ding talk about his dreams of a free, democratic society, gazing at him in admiration like an eager elementary school student. Luo remembered his words about how the imperial system in China had never truly come to an end, and that one of his favorite books was “Doctor Zhivago” for its insights of the essence of human nature and marriage.

She also shared a concern for society. When she walked past the homeless people on the street, she felt embarrassed by her inability to help, yet wondered why the government seemed to be providing little assistance to these vulnerable citizens. Before college, she had wanted to become a teacher and bring education to the most impoverished areas of China. During her annual family dinners, discussions would revolve around recent incidents of injustice that they had heard or witnessed. However, she thought no one expressed their thoughts as eloquently as Ding did.

At that time, she never associated Ding’s vision with politics in the real world, nor did she ever imagine that one day their family would suffer along with his pursuit of civil society. The 24-year old Luo knew only that she loved Ding's idealism and optimistic nature. She felt that she would do anything to support him, and she suspended her plan to study abroad.

Occasionally, she would ask Ding, “Honey, aren’t you exhausted from having all those thoughts swirling in your head all day? Can’t you just relax and enjoy a good life with me?”

“When we enter this world, we’ve got to leave our mark, you know?” Ding would reply. “Otherwise, what’s the point of being here? We’ve got to do something to make a difference, to contribute to the world’s progress.”

What’s the point of being here? This question has lingered in Luo’s mind since childhood. In the first two decades of her marriage, she believed her purpose was to support Ding and their family, to be a good wife, a good mother.

VII.

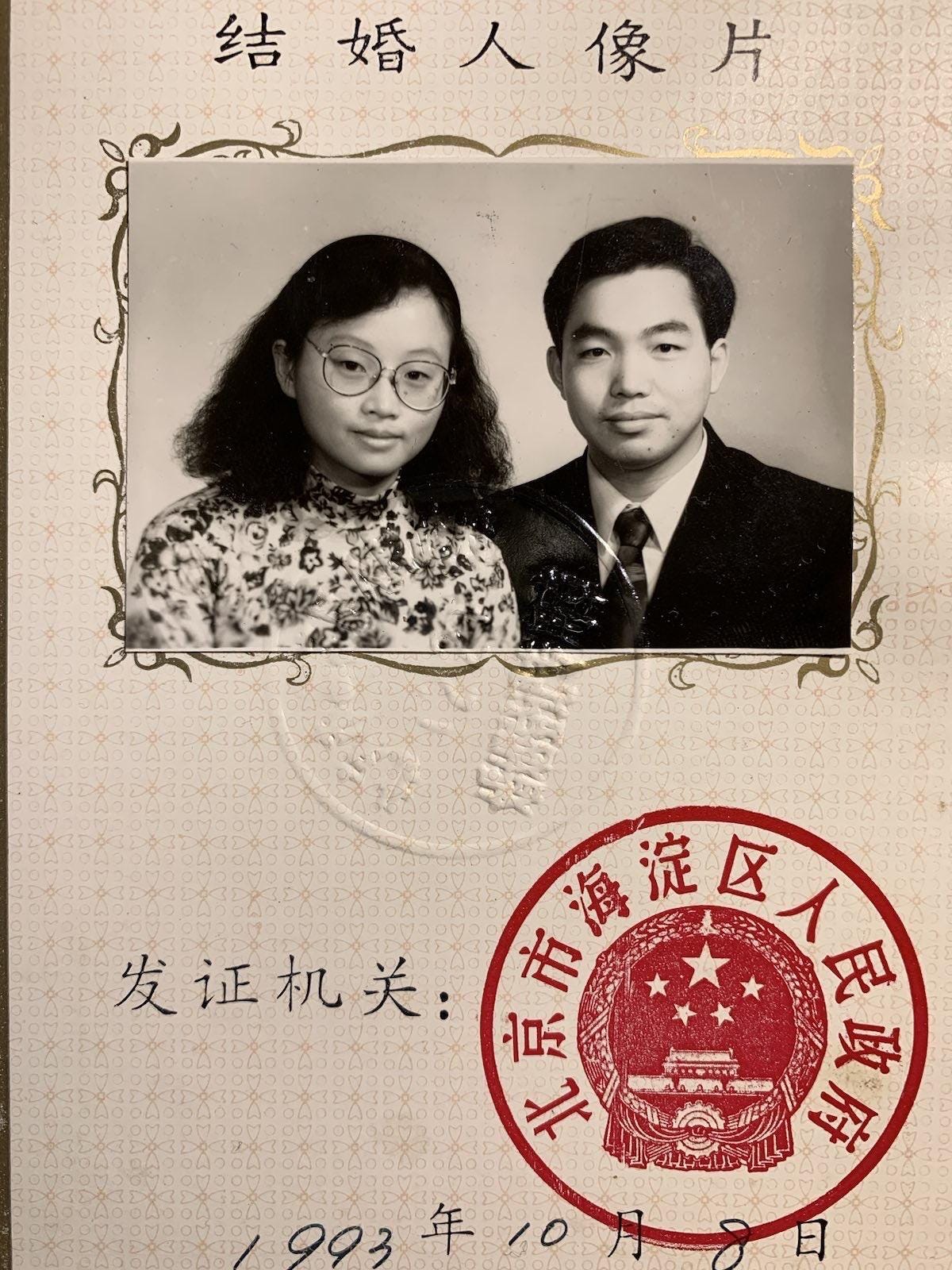

On October 8, 1993, Ding and Luo officially registered their marriage at the Civil Affairs Bureau. Just like many young couples in the 90s, they couldn’t afford an extravagant wedding ceremony with a grand banquet and a lavish wedding gown. Instead, they celebrated by sharing a bag of candies with Luo’s colleagues at the 304 Institute. They also took a simple black-and-white wedding photo at the Civil Affairs Bureau to put on their marriage certificate. Ding was dressed in a suit that Luo had bought for him with her first month's salary, while Luo, dressed in a floral outfit, wore a pair of round glasses and had shoulder-length curly hair.

The Marriage Certificate of Luo Shengchun and Ding Jiaxi, issued on October 8th, 1993

Shortly after their marriage, Ding was also accepted into 304 Institute. In the beginning, their limited budget allowed Ding and Luo to furnish their room with only essential items: a bed, a wardrobe, a television, a table, and a chair. Two years later, when Luo became pregnant, Ding set up a street stall for legal consulting and handed all his earnings to Luo as “formula milk money.”

“We really had to split every penny in half to make ends meet,” Luo said.

Luo didn’t ask for much, whether materially or emotionally. “I’m the kind of person who healed the scars and forgot the pain,” she said. Luo had to sign the consent form with her own trembling hands and undergo the C-Section alone. When Ding finally arrived at the hospital, their first daughter Katherine had already been born. They couldn’t afford a private ward at the time, so Ding had to leave in the evening. Still, when she saw him the next day, carrying a pot of chicken soup and stewed mushrooms, all her grievances disappeared.

Two months after giving birth, Luo returned to work. She enjoyed the daily routines of dropping off and picking up Katherine with Ding at the kindergarten provided by the institute. In 1997, Ding started to work at a program called the Lawyer’s Mailbox at the Central People’s Broadcasting Station, where he responded to over 140 letters from the audience, addressing various legal cases. In the 2017 interview with China Change, Ding said it was a good practice for his professional skills as a lawyer.

October 1997, Luo Shengchun and Ding Jiaxi with their elder daughter at Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China

Things were easy and stable. Those years were the happiest time in Luo's marriage.

To be continued next week.