Due to concerns regarding government repercussions, the writer of this piece writes under the pen name “Sloane Song.” Human Rights in China has independently verified the identity of the writer.

In fall 2017, Ding Jiaxi came to the United States and reunited with his wife Luo Shengchun and their daughters. Despite protests from his family and friends, he returned to China after two months to continue his advocacy for human rights and democracy. On December 26, 2019, Ding Jiaxi was arrested for the second time.

In the third part of Luo’s narrative, we explore her life during the period of Ding’s second arrest. She wanted Jiaxi to come home, and this put her in a more confrontational position against the Chinese Communist Party.

This piece will be published by Human Rights in China one part at a time, over five weeks. Read part one here and part two here.

XVI.

In September 2017, Ding and Luo reunited at Greater Rochester International Airport. It felt like a dream to Luo. She didn’t bother with dressing up or putting on makeup, still uncertain if this moment was real as she made her way to the airport. As Ding opened the car door and got in, he greeted her with simple words, “Hello, my wife.” There were no embraces or handshakes, and during the entire journey back, they didn’t know what to say to each other.

Since Ding’s release in October 2016, his visa applications to visit the U.S. had been - rejected until September 2017. When he finally obtained the visa, he asked Luo to book a round-trip ticket. He intended to stay for only two months.

“I have waited for you for four years,” Luo pleaded Ding. “But you’re only willing to give me two months.”

During the initial days of their reunion, Luo felt disoriented in Ding’s company. She was afraid to be close to him, and didn’t know what to say. Slowly, she began to feel that Ding was no longer a stranger after four years apart; he was her husband, her Jiaxi again. However, simultaneously, she was painfully aware that she would soon have to part with him once again.

Luo said that during those two months, Ding embraced the role of a good husband and father. He took care of household chores, cooking, and laundry, impressively tidying up the house to the point where their daughters marveled at its newfound cleanliness. He joined her for walks, social gatherings, and church services, eager to meet everyone she knew. They danced together, attended art exhibitions, enjoyed music concerts, and walked along every hill in Alfred. He woke up early to practice yoga with her. September and October happened to be the most vibrant months in Alfred, and he accompanied her to experience every bit of it.

Luo shared that while Ding was here, he made progress in improving his relationship with Caroline. They played tennis together, and he even attended her tennis matches at school. However, Katherine still held a grudge against him. She was studying at Cornell when he visited, and they only managed to have a few meals together on campus.

At times, Luo found it difficult to tolerate the habits Ding had developed during his time in prison. He always wolfed down his food so quickly that Luo barely had time to sit down. His constant pacing and contemplation in the room made Luo feel dizzy. He found everything edible fascinating, even the simplest chocolate that Luo considered ordinary; he would want to buy it and give it a try. Luo wanted to say something, but then, considering they only had two months together, she decided to let it go. There was no point in trying to change his behaviors just for the sake of two months.

After staying together for over a month, Luo noticed that Ding started to appear absent-minded. He seemed restless, eager to return to China, as if he stayed any longer, he might not be able to go back.

“Why do you have to go back to China?” Luo challenged him. “As an individual, your power is limited. Only God can change China. You can stay in the U.S. and witness China’s transformation remotely.”

“I feel uneasy here,” Ding responded. “I’d be guilty if I’m here enjoying the life of freedom and democracy while one-point-four billion people in China suffer under authoritarianism and dictatorship. I can’t leave China.”

Every day, they talked about whether he should stay or leave, but Luo was aware that these discussions were futile. She knew she couldn’t force him to stay. She just wanted him to stay a bit longer. She envisioned him staying for two more months until Christmas, when their daughters would be on break. She thought it would be wonderful if he could spend Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year with them.

Luo remembered the time when Ding held her in one arm and Caroline in the other, saying, “Help me figure out how I can have it all. I’m torn in two. I want to be with you both, but my heart is in China.”

Luo said everyone that met Ding tried to persuade him to stay. Her colleagues at Alstom suggested extreme measures like hiding his passport, shredding it, or even burning it.

Luo made the difficult decision to let him go. She understood that if she forced him to stay, their home would become a prison for Ding.

“I thought God had destined him to return to China.” Luo told me.

Her daughters felt otherwise. According to Luo, Katherine would not forgive Ding. She thought Ding turned away from his family responsibilities and failed to be the father or husband this family needed. Caroline was reluctant to mention Ding in her college admission essay. She couldn’t understand why her father would say he loved them, but then chose to leave them for China.

In the end, only Luo drove to the Buffalo Airport to see Ding off. She watched as he waved her goodbye, swung his backpack over his shoulder, and blew her a kiss. “Go back, my dear wife. Everything will be fine,” he said with his ever radiant smile, and then disappeared from her sight.

Luo didn’t know how she drove back. She felt like a knife was cutting through her heart.

In May 2018, Ding wanted to visit for Katherine’s college graduation ceremony. He packed a suitcase full of their cherished memories from China – photo albums, clothes, and gifts he had bought for Luo and their daughters – but upon reaching the border, he was informed that he was on the travel ban list for national security reasons.

Ding and Luo were devastated. In the following week, during some sleepless nights, Ding gathered every photo they had together, refilmed them one by one and stored them on a USB drive, then arranged for someone to bring the USB to Luo.

Luo thought she might never see Ding again in her life. Her body experienced a stress response as the right half often felt as if it had been electrocuted. She believed this was because she no longer felt complete. She had lost a part of her life.

Once again, Ding brought up the idea that he wouldn’t blame Luo if she chose to get divorced and be with someone else. Hurt by his words, Luo implored him to stop saying such painful things.

“Just tell me when you will come home,” Luo pleaded.

After two weeks of contemplation, Ding finally responded, “Give me ten years, my dear wife, starting from the point I was released in 2016. If I cannot achieve my vision in ten years, I will come home to be with you and the kids. In 2026, if I fail, I will find a way to come to you, no matter what it takes, even if I have to leave by sneaking across the border.”

XVII.

According to the “12.26 Citizen Case” report by Human Rights in China, in early December 2019, legal advocate Xu Zhiyong, lawyers Ding Jiaxi and Chang Weiping, along with other lawyers and participants, gathered in Xiamen, Fujian Province, to engage in discussions about current affairs and China’s future, and exchanged their experiences in advocating for the development of civil society.

On December 26, the authorities initiated a crackdown on the participants and other individuals involved in the private gathering. Over 20 lawyers and other citizens were either taken away, summoned, or detained. Some were held under suspicion of “inciting subversion of state power” or “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” Many of those detained were later released on bail pending trial. Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi faced official arrests. Li Qiaochu, who publicly advocated for the release of her boyfriend Xu and others, was summoned for questioning multiple times and eventually detained at an undisclosed location. Lawyer Chang Weiping experienced two instances of residential surveillance at a undisclosed location, where he was subjected to torture, before he was officially arrested.

XVIII.

Many years ago, Luo and Ding had made a pact to visit Hawaii together, and Luo and her daughters had waited for Ding to join this trip since then. In the winter of 2019, they came to the realization that Ding might not be able to join them for a long time, so they set off to Hawaii without him.

On the eighth day of their vacation, while Luo was climbing a mountain on a coastal trail and her two daughters were playing in the water at the beach below, she received a phone call from a friend: On the night of the 26th, a group of police officers had forcibly taken Ding away along with his belongings without providing any legal documents, leaving broken security locks and his apartment in chaos.

Luo’s heart sank. Four hours before Ding’s arrest, Luo was still talking to him on the phone, asking him to try again to visit her in case he had already been removed from the travel ban list. She broke the news of Ding’s sudden arrest to her daughters. Shocked and enraged by the news, her daughters noticed afterwards that Luo was staring blankly, lost in her thoughts. They repeatedly asked her “Mom, are you okay?” but Luo didn’t know how to respond.

They flew back from Hawaii the next day. Luo reached out to her “709 sisters” – accidental activists in China, who had been advocating for their husbands that were taken away during the nationwide crackdown on human rights lawyers that started on July 9, 2015. The crackdown was later known as the “709 crackdown.”

“Please, teach me what to do,” Luo said to her 709 sisters. “I will not stay silent this time. The CCP has way crossed the line, and I have all my time and energy in the world to fight them.”

Her 709 sisters quickly pulled together a group chat and instructed Luo to raise Ding’s case through Twitter. Since Luo signed up for Twitter in 2014, she had only posted twice about her everyday life and once to support her 709 sisters. Luo initially wanted to post once every week, but they told her that she must post everyday. Now she needed to weave each sentence like delicate embroidery to articulate Ding’s case with utter clarity in a few hundred characters.

On January 6, 2020, Luo posted the first video shot by her daughter Caroline. In the video, Luo, dressed in a red turtleneck sweater, sat solemnly on the brown sofa in her home in Alfred, with a table lamp casting a soft glow on her. She announced the news that Ding Jiaxi had been missing for ten days.

“I know my husband very well. He is a gentle and rational person. Despite the thousands of miles between us, we communicate through video almost every day. I'm certain he hasn't done anything that violates the Chinese constitution or laws. On the contrary, it is illegal for the police to take my husband and all his belongings without presenting or sending any legal notice. I have hired a lawyer who will follow leads provided by friends and head to Yantai, Shandong, next Tuesday to find out what happened to my husband. I will continue to report my husband’s abduction by Chinese police to my friends and the international community. Thank you all.”

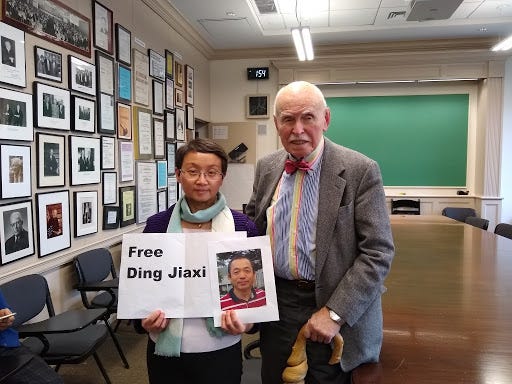

In January, Luo posted her interaction with seven officials at the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, Congressman Jim McGovern, Democrat, Massachusetts, and the founding director of NYU U.S.-Asia Law Institute, Jerome Cohen.

In February, she gave a speech at Alfred University on her family’s connection with Alfred, the crackdown on New Citizens Movement from 2013 to 2014, and Ding’s arrest over a gathering with friends in Xiamen.

In March, Caroline and Katherine each received nearly 30 letters and cards supporting Ding at their schools. Luo sent a petition letter requesting the release of Ding and his friends involved in 12.26 Citizen Case with 32 pages representing 329 signatures from six states in the United States, to Minister Zhao Kezhi of the Chinese Ministry of Public Security, Director Zhao Feng of Yantai Public Security Bureau, and Ambassador Cui Tiankai of the Chinese Embassy in the United States.

By the end of the year, she had sent out letters regarding the 12.26 Citizen Case to government officials and human rights organizations to over twenty countries in North America, Europe, and Oceania.

In 2022, Luo was invited to attend the Geneva Summit for Human Rights and Democracy, where she gave the speech “Losing My Husband to China” and implored the U.N. and the American government to “intervene and say – we know this is a fake case. Release them now or face sanctions.”

Locally, Luo’s friends at the Alfred Union University Church took action by creating eleven videos demanding the release of Ding and his colleagues. In September, the local newspaper, The Alfred Sun, showcased Luo's essay titled "Ding Jiaxi and Alfred," which was originally published in China Change in August, on the front page with a bold headline that read “Free Ding Jiaxi!”

XIX.

Soon after Ding was forcibly disappeared, Luo realized that this time was different from Ding’s first arrest. In 2013, a few days after Ding was taken away by the police, his lawyers were able to meet with him and bring out audio recordings regularly. Legal documents, from indictment to verdict, were delivered to Ding’s lawyers accordingly. From their communication during Ding’s time in prison and after his release, Luo knew that he wasn’t subjected to torture. While she remained convinced of the unjust nature of his sentence, there was solace in the knowledge that his time in confinement hadn’t been marred by severe suffering; he retained basic comforts—access to sustenance, hygiene, rest, reading, and contemplation.

This time Luo and the lawyers barely received legal documentation. Besides a handful of letters rejecting the lawyer’s request to meet with Ding over the excuse of his alleged involvement in “subversion of state power,” an official arrest notice was sent to Ding’s sister in June, 2020. For six months, Luo remained in the dark concerning Ding’s whereabouts and the reason behind his detention. She didn’t know if he was alive. It wasn’t until thirteen months into his detention that Ding was finally permitted to meet with lawyer Peng Jian. Yet this meeting came at the price of Peng being coerced into signing confidentiality agreements that precluded him from discussing Ding’s case with the media, or publicly addressing any aspects of the case.

Upon Luo’s request, I did not reach out to Peng for comment by the time of publication. According to Luo, agreeing to an interview with foreign media outlets would potentially lead to the suspension of Peng’s legal practice license.

In April, 2020, Luo started to write letters to Ding. She was proud that her letters were no longer filled with sorrow and grief, but instead brimming with her determination to fight.

In the beginning, she sent letters via text message to police officer Liu, who was in charge of contacting members of the arrested on behalf of Yantai Public Security Bureau, but received no response from him. For the first thirteen months of Ding’s arrest, he was deprived of the right to meet with a lawyer or correspond with Luo. Left with no other choice, she decided to make these letters public on Twitter and Facebook.

“I told Jiaxi how the pandemic wreaked havoc globally, starting from China.” Luo wrote in an article published on China Change in August, 2020. “I told him that his mother knows he is innocent and who the real culprits are. I told him how spring came late this year. I also told him how my children and I enjoyed our work and life during the pandemic. I told him the blooming forget-me-nots, peonies, orchids, and chives in our backyard. I hoped to share the beauty and hope in our lives with him.”

Luo wrote “May my letter be your sunshine” at the end of those letters.

XX.

On the 179th day of Ding’s arrest, Luo was jolted awake by a nightmare. In her dream, Jiaxi was subjected to such brutal torture that she could hardly recognize him. She couldn’t fathom the toll all the torture was taking on Ding. She prayed that God would watch over her Jiaxi.

After having been disappeared for 392 days, on January 21, 2021, from the Linshu County Detention Center in Linyi City, Shandong Province, Ding spoke to his lawyer Peng for the first time after his arrest via video. In their 30 minute video call, Ding said the following about the torture he experienced during Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location:

“It was in the deep winter when I was arrested. I only had one piece of clothing on me, and was taken away wearing just slippers on my bare feet. It was bitterly cold outside, and I felt like every joint in my body was being pierced by knives.

After the Spring Festival, the police started to play ‘Xi Jinping Governance Strategy: China’s Five Years’ to me on repeat, day and night, for 10 days at the maximum volume.

During my six months of Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, I made zero confession for the first one hundred and three days. For seventy three days I endured sleep deprivation and exhausting interrogations. I didn’t see a glimpse of sunlight for six months. I was under artificial lighting 24 hours per day. I was not allowed to bathe or brush my teeth…

…From April 1st to 8th, I was bound to a tiger bench, with a strap tightly restricting my back and another tightly constricting my waist, making it difficult to breathe. Each day, eight people in four shifts interrogated me from 9 a.m. until 6 a.m. the next day, continuously for 24 hours without allowing any sleep. On April 7th, my ankles swelled like buns, and the pain was unbearable. I suddenly thought of my wife and daughters, so I told the interrogators that I would no longer insist on making zero confession.”

Although Luo had expected torture, the gruesome details of their cruelty still managed to shock her deeply. “This regime has lost all semblance of humanity,” Luo thought, filled with dismay and horror. She realized that Ding's release was unlikely as long as the CCP remained in power.

In her next letter to Ding, she wrote, “My dear husband, rest assured, I will not let them get away with this. I won’t allow you to bear this pain in vain.”

Tears, sighs, and grief are futile. Luo realized. Only through struggle and fighting back can I save my Jiaxi.

To be continued next week.