The “Collapse” of Journalism: How Different Generations of Journalists Document China

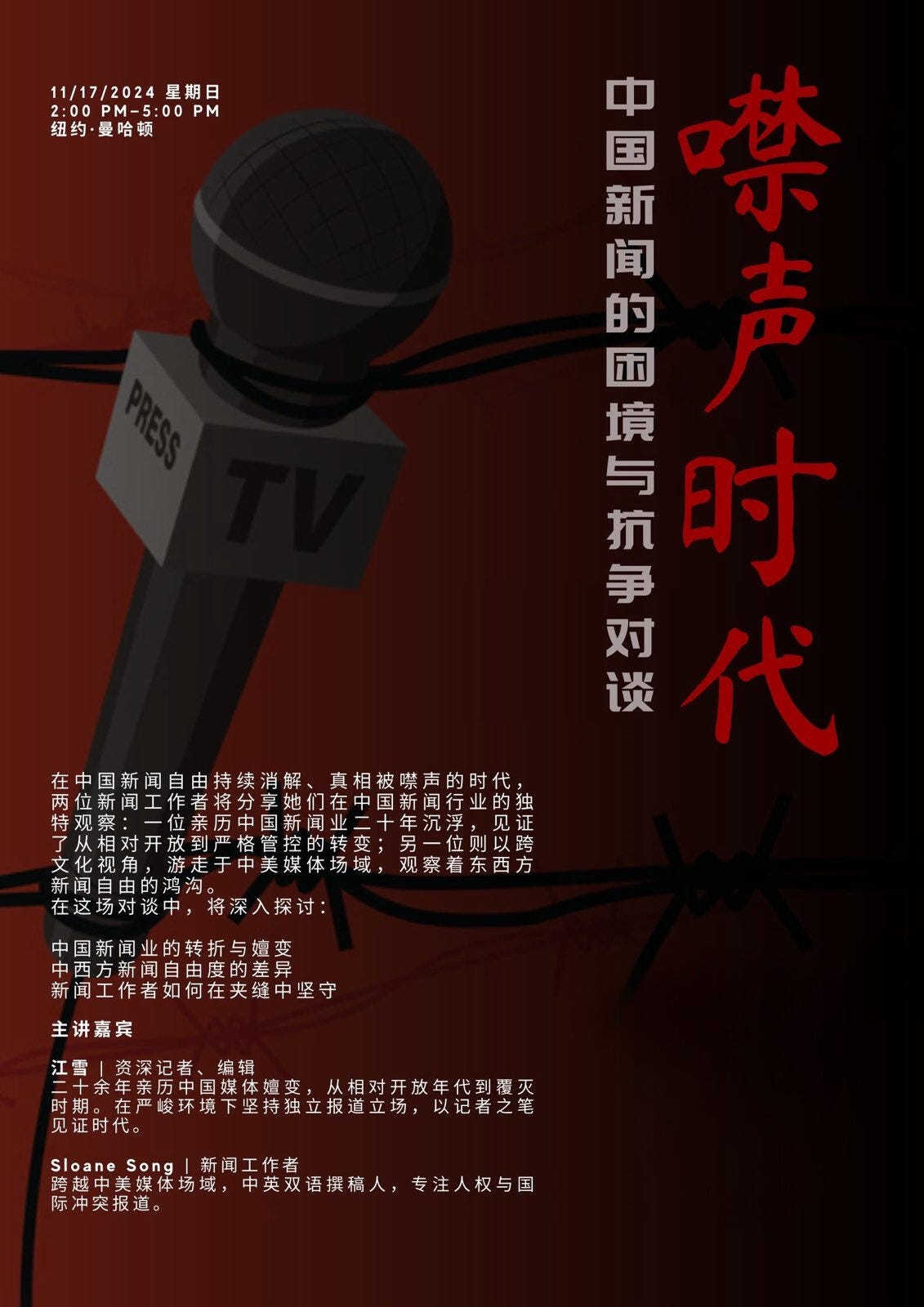

On November 17, 2024, Human Rights in China hosted a symposium titled “The Age of Silence: A Conversation on the Plight and Resistance of Chinese Journalism.” Two Chinese journalists, Jiang Xue and Sloane (a pen name), shared their experiences in mainland China and discussed the long-standing censorship challenge faced by the Chinese journalism industry, the industry's unfriendly attitude towards young journalists, and more.

后附中文版

"Journalism has already fallen"

Sloane is a member of Gen Z, and her experience during the COVID-19 pandemic was the main reason she became a journalist. When COVID began, she was still in high school in mainland China. School was suspended, and she stayed at home every day, relying on her phone to get updates about the pandemic. "I suddenly discovered that I really needed news. I needed a trustworthy media source to tell me the real statistics, tell me whether I needed to wear a mask when going out, and tell me whether the materials donated to Wuhan had been distributed to the citizens." However, she was unable to find a news platform that would give her this information.1

It was this experience that made Sloane realize the significance of journalism work. Later, she started working on oral history, recorded individual stories, and read manuscripts published by Southern Weekly during the heyday of [Chinese mainland] news media. Then, she took a media internship and became a reporter herself.

When the pandemic hit, Jiang Xue had been working in the news industry for more than 20 years. After experiencing the news industry’s golden era, she transitioned into an independent reporter in 2015. At the end of 2021, her piece “Ten Days in Chang'an,” which described her experience during the lockdowns in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, became a widely circulated article during the pandemic. After that, she said resignedly, she had reached a point of “no way out” as an independent reporter in China.

During the symposium, Jiang Xue repeated one phrase many times: "Chinese journalism has already collapsed." She recalled that from the late 1990s to around 2015, the news industry was still fighting government censorship. In contrast, the industry has now given up on resistance and only wants to survive. She emphasized that even during the so-called golden age, censorship and rejection of manuscripts were the norm every day, but reporters during that era still tried to push the red line. Even more sad is the fact that many reporters have left the news industry, and excellent talent is unwilling to step foot into the field.

Sloane recalled that when she was interning at a news agency, almost all the reporters repeated the same thing: you can't do news in China. The experience that left her with the deepest impression was when a reporter was going on a business trip and had already bought a train ticket, while Sloane was collecting information and reaching out for interviews behind the scenes. But when the reporter was on the way to the train station, the censorship order came, and Sloane received a frustrated message: "There is no news in China."

Censorship is not the only problem

After six months of her journalism internship, Sloane realized that the problems with China's journalism go far beyond censorship. “After returning to China, I found that interns are a cheap, even free, labor force.” The editorial department where Sloane interned had a large number of people. During meetings, editors and reporters sat at a table, and interns could only sit on the periphery.

In fact, when Sloane was studying overseas, she had interned at another news company. There, the editors treated interns and full-time reporters the same, and the resources were divided equally. "Whether I wanted to cover any topic, I wanted to go on business trips, I wanted to take a taxi, or I wanted to interview people anywhere, they fully supported me with both energy and money."

But in the editorial offices of Chinese media, interns are like invisible people. If they don't actively raise their hands to report, they will be skipped entirely during meetings. Sometimes, reporters don't necessarily need the assistance of interns, and the job of the interns becomes to help find interviewees on various social media platforms. After an intern makes contact successfully, the interviewees’ contact information will be sent to the reporter. In the end, the manuscript will not be signed with the intern's name, and no manuscript fee will be shared. Sloane bluntly said that this kind of work is just repetitive labor which does not help newcomers in becoming reporters, and the atmosphere of treating newcomers this way is even more disheartening.

The focus and interests of Chinese media have also narrowed. Sloane concluded that the topics that editors prefer are mainly related to the lives of the middle class in big cities. For example, major disasters in remote areas will be labeled as “unimportant,” even if hundreds of thousands of people are affected, and important topics in the international community are also seen as something no one cares about. “The media doesn’t want to set any historical agenda. They just think that if it’s something urban middle-class readers are interested in, they just need to write it in a sufficiently exciting way and find some public value in it,” Sloane concluded.

This sort of media atmosphere and style of topic selection are very different from Jiang Xue's early years. Jiang Xue studied law, and when she first started working as a reporter, senior reporters were very active in guiding newcomers and were willing to give newcomers opportunities. Therefore, as long as they independently reported on a few news stories and senior reporters helped them revise their manuscripts, newcomers could rise through the ranks quickly. In addition, the media at that time had a sense of responsibility. Even though the Chinese news media has never been given freedom of speech under the censorship machine, the news industry at that time still had the desire to try to change the country, “to use the ‘draft of history,’ that is, the news, to influence our present, in order to move China forward a little bit, improve the environment a little bit, and give the public a little more access to information."

Jiang Xue believes that a responsible news industry is closely linked to the entire civil society. In the past, the media, lawyers, and scholars had close cooperation; a relationship of mutual response, mutual encouragement, and moving forward together.

At present, the censorship pressure faced by Chinese media does not only come from the government. Sloane once proposed a topic about a well-known company's employment problems at a topic proposal meeting. The editor responded vaguely and the topic was not approved. After the meeting, Sloane learned from other colleagues that this company was a business partner of the media company she worked for, so they could not publish negative news about the company. This kind of “financial sponsor” affected the media's supervision of the company. This is a common situation at the current moment, when the media is facing difficulties in revenue.

Opportunities for Chinese media in the future

Despite all these problems, participants in the symposium also wanted to discuss what areas there still are for breakthroughs in Chinese news. Some people asked, is it feasible to bypass censorship by publishing information overseas and then transmitting it back to domestic readers?

Jiang Xue believes that although WeChat, Weibo and other social media commonly used by mainland Chinese users are strictly censored, it is still possible to “slip through the net.” As long as news reports can be published, the information may be spread on domestic social media in the form of screenshots, documents, and so on. The Chinese authorities even call this “overseas backflow.” In addition, regardless of the conservatism and regression of media organizations, there are still many journalists in China who work hard on the front line of news reporting and overcome obstacles to cover news on the ground.

Symposium participants expressed that the Chinese people themselves are also dissatisfied with the fact that news is inaccessible. In other words, the people need news, but the risk of reporting is getting higher and higher.

Another scholar working in the academic community mentioned that since journalism is closely linked to the rule of law and civil society, journalists need allies. “When reporting on an issue or wanting to direct public attention to an issue, journalists often find various allies to expand their viewpoints or give their voices a stronger sense of legitimacy and legality.” For example, when it comes to reporting, scholars and experts may be called upon to give their opinions on some specialized topics.

However, Jiang Xue believes that it is becoming increasingly difficult to form "alliances" in China because scholars and experts are becoming less and less willing to speak out, and it is difficult to return to the era when civil society expressed itself cooperatively as a community.

In contrast, one participant felt that we should not be too pessimistic, as reality may not be as bad as imagined. She said: “Censorship, fear, and intimidation are all methods of totalitarian rule. I think what is more serious now is that this kind of self-censorship and self-imposed fear have reached a very concerning level.”

“覆灭”的新闻业:不同世代的记者如何记录中国

2024年11月17日,中国人权主办了“噤声时代:中国新闻的困境与抗争对谈”的座谈会,两名中国记者江雪和Sloane分享了各自在中国大陆从业的经历,并讨论了中国新闻业长期面临的审查困境、行业对年青记者的不友好等等。

“新闻业已经覆灭”

Sloane是千禧一代,新冠疫情期间的经历是她成为新闻记者的主要原因。新冠开始时,她还在中国大陆上高中,学校停课,她每天都在家中,靠手机资讯了解疫情动态,“突然发现我很需要新闻,需要一个可以信任的媒体来告诉我一个真实的数字,告诉我需不需要戴口罩出门,告诉我捐到武汉的物资有没有发到市民的手里?”然而,她并没有找到一个能告诉她这些资讯的媒体。

正是这段经历,令Sloane意识到做新闻的意义。后来,她开始做口述史,记录个体的故事,又读了南方周末在新闻媒体繁盛期刊出的稿子,后来她到媒体实习工作,成为一名新人记者。

同是新冠期间,江雪已经在新闻界做了超过20年,经历过新闻业蓬勃发展的年代,她在2015年转型成为独立记者,2021年年末,她描述陕西省西安市封城经历的《长安十日》成为疫情期间传播甚广的文章。她无奈地表示,其后她作为独立记者在中国已经到了“无路可走”的境地。

在对谈期间,江雪多次重复着一句话:“中国的新闻业已经覆灭。” 她回顾在90年代末到2015年前后,新闻业还是在对抗审查,反观当下,行业已经放弃了抵抗,只求存活下来。她强调即便在大家口中的黄金时代,审查和毙稿也是每天的常态,只不过当时的记者还试图去挑战红线。另外,更可悲的是,很多记者已经离开了新闻业,而优秀的人也不想踏入这一行。

Sloane回忆起,她在新闻机构实习的时候,几乎所有记者都重复着一个论调——在中国是做不了新闻的。印象最深的一幕是,一个记者原本要到外地出差,车票都买好了,而Sloane正在后方收集资料、联系采访,可是记者正在去往火车站的路上,禁令就到了,Sloane收到那名记者沮丧地发来消息:“中国是没有新闻的。”

審查並非唯一問題

经过半年的媒体实习,Sloane意识到,中国新闻业的问题远不只有审查。

“回国后,我发现实习生是一个廉价,甚至免费的劳动力。”Sloane实习的编辑部人数很多,开会的时候,编辑和记者坐满一桌,而实习生只能在外围。

其实,Sloane在国外留学的时候,也在新闻媒体实习过,编辑对待实习生和正职记者都是一样的,资源也是平等的,“我想做任何选题,我想出差、我想打车、去哪里采访人,他们都是从精力到金钱上完全支持。”

可是在中国媒体的编辑室里,实习生像一个透明人,如果不是很积极地举手报题,开会的时候就会被直接跳过。有时候,记者也不一定需要实习生协助,最后实习生的工作就变成在各种社交媒体上帮手找采访对象,联系成功后,再把联系方式发给记者,最后稿件也不会署有实习生的名字,也不会分得稿费。Sloane直言,这种工作只是重复劳动,对新人成为记者没有什么帮助,而如此对待新人的氛围更是令人心寒。

中国媒体的关注点和兴趣也变得狭隘,Sloane归纳,编辑们喜欢的选题主要是与大城市的中产生活相关,例如,发生在偏远地区的重要灾害会被贴上“不重要”的评价,哪怕有几十万人受灾;国际社会的重要话题也被认为是“没人关心”。“这些媒体不想设置任何历史议程,他们只是觉得,城市中产读者感兴趣的,就把它写得足够精彩,在里面找一些公共价值就好。”Sloane总结。

这样的媒体氛围和选题审美与江雪早年从业时大相径庭。江雪毕业于法律系,刚刚入行做记者的时候,资深记者都很积极地带新人,也很愿意给新人机会,所以只要独立跑过几个新闻,资深记者再带着改稿,新人很快就可以成长起来。另外,责任感是新闻媒体的一个共识,哪怕在审查机制下,中国新闻媒体从未得到过言论自由,但当年的新闻业还是有着试图改变这个国家的愿望,“想用‘历史的草稿’,就是新闻,来影响我们今天的当下,能够让中国稍微往前走一点,让环境改善一点,让公众的知情权多一点。”

江雪认为,有责任感的新闻业也和整个公民社会息息相关,以前媒体和律师、学者都有紧密的合作,是一种互相呼应、互相鼓舞,一同向前走的关系。

当前,中国媒体面临的审查压力也不仅来自于政府。Sloane曾经在报题会议上,提出一家知名企业存在用工问题的选题,编辑含糊回应,选题也没有通过。会议后,Sloane从其他同事处了解到,这家企业是其供职媒体的商业合作方,因而媒体不能发布该企业的负面消息。这种“金主”影响媒体对企业的监督,在媒体营收困难的当下,也是常见的情况。

未来中国新闻的机会

种种问题之下,活动的参与者也想讨论中国新闻还有哪些突破的空间,有人提出,在海外绕过审查发布资讯,再传回给国内的读者是否可行?

江雪认为,尽管微信、微博等国内用户常用的社交媒体审查严格,不过还是有“漏网”的可能,只要新闻报道能发布出来,信息就可能以截图、文档等形式,在国内社交媒体中传播,中国官方甚至将此称作“境外倒灌”。此外,抛开媒体机构的保守和退步,国内仍旧有不少记者在新闻报道的一线努力,突破困难到达现场。

参加者们也认为,中国民众对于这种消息被封闭的情况,也同样是不满意的,换句来说,民众是需要新闻的,只是做报道的风险变得越来越高。

另一名在学术界工作的学者提到,既然新闻业和法治、公民社会紧密联系,那么记者是需要“同盟”的,“记者在报道一个议题,或者想唤起公众对某一个议题关注的时候,往往会找到不同的同盟来扩展自己的声音,或者给自己的声音一种更强烈的正当性、合法性。”例如在报道的时候,需要学者、专家就一些专业问题提出意见。

不过,江雪认为在中国国内越来越难形成“同盟”,因为学者、专家变得越来越不敢说,公民社会作为一个共同体,一起去表达的时代,已经难以重现。

有参加者则认为,我们不应过于悲观,现实可能并不像想象的那么糟糕。她提出:“审查和恐惧、恐吓,都是极权的统治手段,我觉得,现在更严重的是这种自我审查和自我恐惧已经到了非常严重的地步。”

世界日報: "不同時代記者分享中國新聞業的衰敗 談親身經歷的管制、審查"

Editor’s note: The Chinese authorities strictly controlled all information flows during the pandemic, hoping to maintain social stability and uphold the legitimacy of the CCP. This censorship created a vacuum of reliable data which left citizens confused, fearful and vulnerable.